The shiny barrier of luxury that once clearly defined social and cultural classes has for the most part fallen by the wayside. These days even the most average of incomes can support some level of Tiffany, Cartier, Hermes, Asprey, Gucci, or Louis Vuitton.

The shiny barrier of luxury that once clearly defined social and cultural classes has for the most part fallen by the wayside. These days even the most average of incomes can support some level of Tiffany, Cartier, Hermes, Asprey, Gucci, or Louis Vuitton.

Only one generation ago any of these names would conjure up images of drivers waiting outside intimidatingly luxurious store fronts. Most luxury labels were aspirational in the truest sense; you could dream but never really achieve. Such stores were the definition of exclusive. They were out of bounds for the ordinary consumer. You could walk in of course, but you didn’t really belong there.

How the world has changed. Though many of these companies took generations to become the bastions of excellence and good breeding that defines their brand’s DNA, it took a relatively short period of time to make many of their products and accessories available to the masses. When once only New York’s privileged scions browsed for the perfect diamond engagement ring, today every other teenage girl has a “Return to Tiffany” bracelet or Paloma Picasso necklace.

How the world has changed. Though many of these companies took generations to become the bastions of excellence and good breeding that defines their brand’s DNA, it took a relatively short period of time to make many of their products and accessories available to the masses. When once only New York’s privileged scions browsed for the perfect diamond engagement ring, today every other teenage girl has a “Return to Tiffany” bracelet or Paloma Picasso necklace.

In their drive to reach the ultimate brass ring of market share, sobriety and tradition gave way to down market sales. Catch them young, the theory goes; let them afford a hat, tie, scarf, or bracelet with the coveted logo on it, and when they grow up and make more money they’ll come back to spend it on a sapphire necklace, suit, or an iconic trench coat. And it worked.

At least the first part worked. The problem of course, is that when you have lots of people with cash – or more often credit – and a desire for for their own “influencer” Instagram feed, the more bling they can sport the better. What began as an effort to ensnare more customers and grow the bottom line quickly twisted into outright brand saturation.

The turning point for venerable Tiffany & Co., apparently came a few years ago when hordes of cash-flushed teens clogging up the “rear salon” – where the sterling silver jewelry and accessories are sold – started to turn off the customers who were coming in to buy the big stuff in the “front salon.” This is where the real action happens; the nice fellow who drops $50,000 on a charming tennis bracelet for his wife.

Since more people could afford a piece of the dream, demand dramatically increased. So did the sales; they just weren’t the type of sales that supported Tiffany’s blue blood image. Brand value began eroding.

After a lot of internal debate, Tiffany’s response was to increase the prices of those very same sterling silver product lines which have been the driving force behind its strong revenues. It was a first really; a luxury company deliberately attempting to drive down sales in it’s most broadly profitable product category as a means of preserving the company’s overall exclusive cache.

Tiffany is now building up it’s social properties and re-framing it’s traditionally jewelry-only glam shots with a more lifestyle, Instagram-able focused approach. Social media and non-corporate influencers are the paths forward, even for for rarefied brands.

Ralph Lauren has experienced a similar soul-searching moment. When the iconic blue label – and all the sub-brands tied to it – is everywhere and the Polo pony seems a bit too commoditzed, it’s time to pull up the drawbridge. They are closing stores, including the vaunted 5th Avenue menswear focused flagship, opened with much fanfare only a few short years ago, and looking for ways to go more exclusive once again.

Ralph Lauren is a particularly interesting case because while it was originally founded as whole cloth luxury aspirational brand, it’s very “this could be you” ethos – literally buying into an exclusive lifestyle – led to a duel-track identity. There was always the “salon” part of the brand that catered to the well-heeled high-flyers. But, they also created numerous lines targeting specific demographics and price points that allowed the company to effectively micro-target luxury access.

But even as this “affordable luxury” trend spread across the luxury market writ large, from entry level Jaguars to entry level monogrammed made-to-measure dress shirts, the inevitable started to happen. The truly rich, the top level consumers started to feel not so special. In RL’s case, his stuff was everywhere across every market sector, and the lack of exclusivity led even devoted fans to question the brand’s actual relevance.

Because if everyone can be special, than, really, no one is special. If everyone is a self-described style expert with an audience and there’s an outlet store in every other mall, the brand really isn’t telling its own story. If I can eye that sharp outfit in a corporate marketed name brand store window and then order up a close, cheaper version from my phone, it’s all about my idea of my style, not Ralph Lauren’s.

Top tier customers started looking for material fulfillment elsewhere. And even upper middle class customers who can truly afford luxury goods as investment pieces, like MTM suits or handcrafted leather bags, began to look elsewhere for quality makers most folks haven’t heard of.

Top tier customers started looking for material fulfillment elsewhere. And even upper middle class customers who can truly afford luxury goods as investment pieces, like MTM suits or handcrafted leather bags, began to look elsewhere for quality makers most folks haven’t heard of.

This is the conundrum facing a number of large luxury houses as we head into the holiday season: the target market they have spent years trying to attract – the aspirational buyer – is not feeling much of a need to aspire to an over-saturated luxury market. And the elite customers, who could set the balance sheet in order with just a few shopping trips, no longer desire many of those brands because it has been watered down.

The result of this shift is equally as fascinating. New designers and real craftsmen are starting to make their mark. People both average and wealthy want something new. Those with the means to have pretty much anything they want, want something no one else has. Average consumers who have money but are now more selective want something unique.

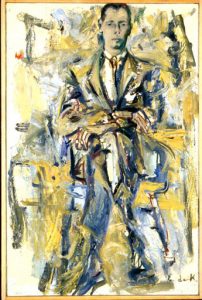

Visionaries like Tom Ford and saw this coming and acted early. After leaving Gucci, Ford decided that New York needed a super high-end men’s clothier that felt like a very exclusive private club, also housed in its own townhouse. you might learn to recognize the Tom ford cut and drape, but you won’t see a label or branding.

Wealthier shoppers are moving way from brand name luxury because it’s simply too common; luxury itself has become a commodity. We are starting to see another shift in the definition of luxury that in some ways point back in time.

When everything is branded, instagrammed, and documented, the only real way to be unique is to disregard labels and logos altogether. Real style is a very personal thing and luxury items are the most extreme expression of personal style. So, in a sense we are back at the beginning when true luxury did not have a label slapped on it, when a suit was handmade and the man wearing it was an ambassador of the tailor, not the tag.

When you get down to it, those who have a real understanding of style don’t need labels. They don’t care if you recognize their bag or their tie or their coat. It’s not about impressing you; it’s about standards they set for themselves. That’s luxury.